Reinhardt's unique collection of engravings, etchings and paintings can be found in the Gallery of Etchings (today known as the Print Room) and the Venetian Room. It is worth mentioning in this context that the first owner of the palace, Count Laktanz, also kept a gallery of paintings, in which works by Ferdinando Galli da Bibiena, Pietro Longhi and Giovanni Domenico Ferretti were displayed.

Since it is not permitted to remove objects that are firmly affixed to the fabric of a building when the property is sold, the pictures screwed into the panels of the Print Room as well as those in the Venetian Room have been preserved.

The Print Room is a small gem of a hallway that leads into the Venetian Room. In 1930, it was paneled in walnut by Anton Widerin, a cabinetmaker from the Itzling district of Salzburg. Widerin then secured the etchings to the panels. In the 1930s, he also installed wood paneling in Café Tomaselli and, after 1945, the pews and confessional boxes in Salzburg Cathedral, which had been bombed during the war.

A total of 69 etchings and paintings from the 17th and 18th centuries depict images such as baroque theater scenes by Ferdinando Galli da Bibiena (1656–1743), which are notable for their strict proportions, perspective and spatial composition.The etchings by Ludovico Burnacini (1636–1707) show playful and light-hearted scenes from the world of rococo opera.

The collection also includes vedute (detailed cityscapes) of Venice, fairground scenes, and baroque celebrations. Depictions of baroque garden theaters probably served as inspiration for Reinhardt’s own garden theater.

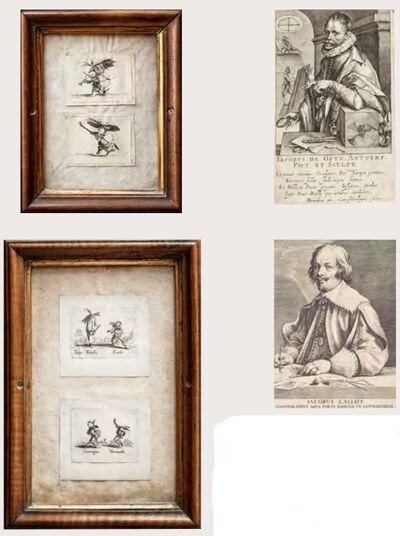

One particular highlight is the 11 etchings by Jacques Callot (1592–1635), which are among the 24 etchings that survive from the famous “Balli di Sfessania” series. These are considered some of the most important depictions of the Italian commedia dell’arte, full of dance-like virtuosity and boisterous fervor.

The Callot collection is complemented by 12 from a total of 21 existing “Gobbi” etchings (portraits of dwarfs).

Perhaps the greatest treasure is an extremely rare series of masks from around 1600 by the Antwerp engraver and painter Jakob de Gheyn II (1565–1629). De Gheyn II was one of the most esteemed engravers of his time, but devoted himself exclusively to oil painting from the age of 40. There are only five known owners of this series of masks.

Max Reinhardt

Max Reinhardt and Schloss Leopoldskron can rightly be called a love story. No anniversary or speech in tribute to the director goes by without quoting his reminiscences of the palace—memorable lines that he penned with ardent passion one late summer in New York, an ocean away from his former Salzburg home:

“I lived in Leopoldskron for eighteen years, truly lived, and I brought it to life. I lived as one with every room, every table, every chair, every lamp and every picture. I built, designed, decorated, planted; and dreamed of the place when I wasn’t there. I loved it in winter and summer, in spring and fall, both alone and with company. I always loved it in a festive way, never as something mundane. Those were the most beautiful, rewarding and vital years of my life and they bear your name” [this was addressed to his wife, Helene].

“It was one of the loveliest and liveliest houses in the world. But it was only a house. I lost it without complaining. I lost everything that I put into it. It was the harvest of my life’s work. I was able to keep on living, well and happy, safe and sound.”

“It was only a house …” These last lines in particular are often quoted—as comforting proof of the director’s stoicism in life. The experience of losing everything and being driven out of his homeland could not really hurt this great artist, or so it seemed. However, if one reads Reinhardt’s letter in full, taking in the many pages through to the end, something else is conveyed: namely, the deep despair of a man who feels betrayed and robbed—of Leopoldskron, the crowning achievement of his life.

But who was Max Reinhardt and what was his story? For the Salzburgers, he was a Jew from Germany; a Berliner. Or was he Viennese? (He actually grew up in Vienna, which for the Salzburgers was admittedly only a marginal improvement). One thing was certain: he arrived as an Austrian who had carved out an astounding career in Prussia. As a young man in Berlin, a buzzing metropolis on the up, Reinhardt absorbed everything—discussions in cafés, new artworks in galleries, and especially music. He was filled with amazement for the latter and happily turned to it again and again, thriving from the exposure to Berlin’s concert halls and theaters at the turn of the century. In the first five years of the new century, between 1900 and 1905, Max Reinhardt became the figure that we remember today. In this short period of time and with dazzling momentum, a self-doubting and unsure young actor who didn’t even have a high school diploma transformed himself into an ambitious artist and entrepreneur, a famous director and impresario.