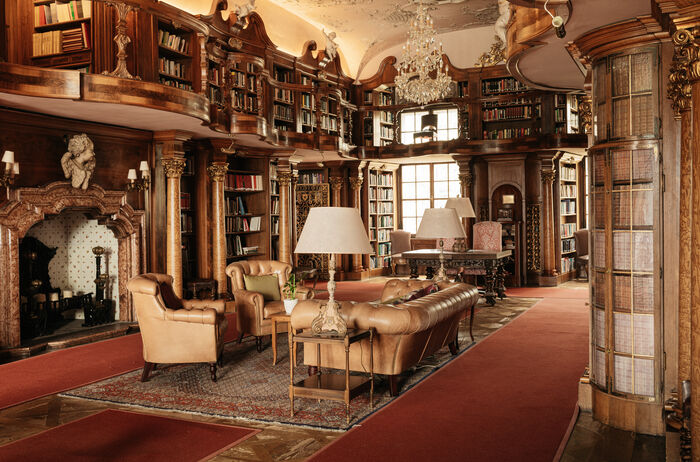

Max Reinhardt (1873–1943) loved spending time with guests in the library from late dinner time until the early hours. He radiated calm, was relaxed, and delighted those he spoke to with his “undivided, warm-hearted attention.” He was highly alert, asked questions, and exuded an “ever greater state of contentment”, according to his wife Helene Thimig (1889–1974).

One evening in September 1930, Carl Zuckmayer was the only guest in the library. In the course of the night, Reinhardt asked him what he was currently working on. Zuckmayer already had parts of The Captain of Köpenick in his head but had yet to set pen to paper. Inspired by Max Reinhardt’s attention and encouraged by his interest, Zuckmayer began to talk him through the play. He fleshed out each scene with all the characters, creating “[new] situations, dialogues, scene endings—the piece was there.” It had “taken shape … through Reinhardt’s magical listening."

The warm wood of the bookcases, their symmetrical arrangement, and the harmonious proportions of the room create an atmosphere in the library that promotes fruitful conversations and the sharing of joy—in one’s fellow human beings, books, music, and the fine arts.

Reinhardt had visited the magnificent Abbey library of St. Gallen in Switzerland and had never

forgotten it. Years later, he created a library with a comparable sense of harmony in Leopoldskron. However, this room not only served as a place to store his books, but also became so essential for spending time in the company of friends that it still forms “the beating heart of the palace.” Max Reinhardt succeeded in recreating the overall effect of the St. Gallen library in Leopoldskron despite differing room dimensions and light incidence. This was based on:

- The proportions of the bookcases and the hue of their wood, as well as the design of the columns with their capitals,

- The alternating convex and concave curvature of the gallery and its graceful balustrade, as well as the veneer on the room-facing sides,

- The form and painted decoration of the domed vault ceiling.

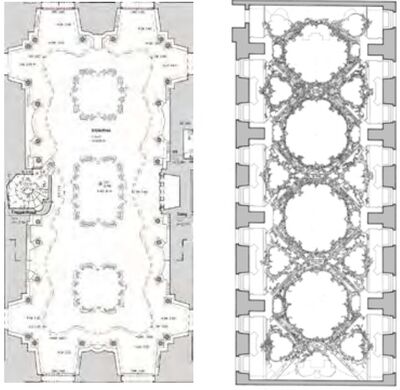

The Leopoldskron library has an internal width of 7.5m (St. Gallen: 10m) and an internal length of 15.8m (St. Gallen: 28m). Both libraries are symmetrical relative to the longitudinal axis, but St. Gallen is longer than Leopoldskron. The positioning of the windows and their number also differ significantly.

As with his theater work, Max Reinhardt entrusted the realization of his vision to strong artistic personalities: the technical planning was carried out by the renowned Berlin architect Alfred Breslauer (1866–1954), who was assisted by the stage designer Ernst Schütte (1890–1952), whom Reinhardt held in particularly high esteem. Reinhardt made sketches of details that were important to him and wrote lengthy letters to Breslauer. Incidentally, Reinhardt kept a sketch and idea book for more than two decades (ca.1922–1943), which contains hundreds of drawings, “a unique document of Reinhardt’s visual, artistic and creative power from his most mature period of life …. Several design sketches for the Leopoldskron library (with a magnificent globe in the center of the room) deserve special mention.” The remodeling of the library lasted from 1926 to 1927.

Prior to the remodeling, the space had been two separate rooms with two windows each, divided by a load-bearing partition wall. Two large rectangular tiled-covered cocklestoves, glazed in green and decorated with strapwork, stood in niches. The ceilings of these rooms were stuccoed with curved, hollow frames. When the load-bearing partition wall was removed, iron crossbeams had to be installed for structural support. In addition, the southwest part of the service area adjacent to the banquet hall was integrated into the library as a study.

Max Reinhardt wanted direct access to his rooms from the floor above the library so that he would not have to go up the main staircase or the servants’ stairs. Access to this staircase is hidden behind a semicircular glass door with false book spines. It was also possible to acquire an attractive parquet floor from nearby Schloss Ursprung and have this laid in the library.

Two experienced stucco plasterers from Salzburg, Rupert Strasser and his son Albert, stuccoed the ceiling. The cartouches contain depictions of the Hohensalzburg Fortress, the horse tamer from the Salzburg horse pond (Pferdeschwemme), and comedy and tragedy masks with the facial features of Max Reinhardt. On the ceiling, two old paintings bought from an art dealership were fitted into three newly made stucco frames. These paintings show Archangel Michael and the four Evangelists.

The library is designed symmetrically in all its parts. The Salzburg carpenter Anton Widerin made the bookcases and their cornice tops, the round pilasters and capitals, and the gallery balustrade. He produced tables and leather-upholstered chairs for the library and also added wall paneling made up of square and rectangular panels, gilded capitals and a cupboard-like cabinet to Max Reinhardt’s adjoining study. His metal wing doors are painted on the inside with depictions of six angels. This room is not just an “office”. It follows in the tradition of the humanistic “studioli” of Italian Renaissance princes.

The library held around 15,000 books and was divided into 18 sections. The section on “German Literature” took up a good third of the library, followed by “Theater Literature” and “French Literature” (each about an eighth), and “English Literature” (about a tenth).Specific shelves were dedicated to Johann Wolfgang Goethe and William Shakespeare. Max Reinhardt designed the labeling for the bookshelves himself. He tasked Gusti Adler with devising an alphabetical system for the library, obtaining books, and attending book auctions. “Please obtain the fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm (and Hauff) in German as soon as possible. A good biography of Benjamin Franklin is also necessary. I would also be very interested in everything that is available in the libraries about the commedia dell’ arte.” In an antiquarian bookshop in Berlin, she discovered the library of the Vienna Burgtheater actor Josef Lewinsky (1835–1907), whom Reinhardt had held in high esteem since his early days in Vienna, which he spent in the standing section of the Burgtheater. The Leopoldskron library grew from the core of Lewinsky’s library, as “it contained everything that pertained to the theater: above all, the literature on the Hanswurst popular theater, valuable first editions of old plays, classics etc.” Reinhardt also owned many works about old folklore, the commedia dell’arte, complete editions of plays by classical and contemporary authors in several languages (in particular, first editions with personal dedications), and a collection of important German-language theater journals.

The books in the Leopoldskron library found their way to the United States after the war. Reinhardt’s sons sold them to the State University of New York at Binghampton in August 1969, along with director’s notes, correspondence and other written materials from their father.

75 Years in 12 Vignettes

With 75 years behind us and more than 40,000 Fellows in 170 countries, Salzburg Global obviously has many stories to tell. The following 12 vignettes have been selected not only for their ability to relate the history of the institution, but also to convey the unlikely symbiosis of a visionary enterprise, conceived at an American university that came to be situated in an eighteenth-century rococo palace in the heart of Europe with the goal of serving the global good.